Why America Reallocates Public-Use Airports

By Scott Spangler on May 23rd, 2017 Public use airports are an essential (and underappreciated) component of America’s infrastructure. The current total, provided by the the Bureau of Transportation Statistics, counts 5,145 public use aerodromes. What’s really interesting about this timeline is the increase between 1980 and 1985, from 4,814 to 5,858 public use airports. The total dropped to 5,589 in 1990, the next stop on the timeline before the annual counts reveal a trend of small and steady decline.

Public use airports are an essential (and underappreciated) component of America’s infrastructure. The current total, provided by the the Bureau of Transportation Statistics, counts 5,145 public use aerodromes. What’s really interesting about this timeline is the increase between 1980 and 1985, from 4,814 to 5,858 public use airports. The total dropped to 5,589 in 1990, the next stop on the timeline before the annual counts reveal a trend of small and steady decline.

The sudden increase in airports between 1980 and 1985 surprised me because it came after general aviation’s leap off the economic cliff in the late 1970s and early 1980s. Search as I might, I could not find a concise summation of why this period experienced a boom not unlike the increasing number of babies born after World War II. Until I find something more authoritative, I’m settling for the logical conclusion that airports aren’t born and don’t die overnight, so the boom was the result of poor timing and the interval of new airport gestation.

My research did reveal interesting examples of why airports die, and why new ones are born in this era of economic stasis for our infrastructure, either maintaining what exists or adding to it.

A community of 28,603, Banning, California, is 80 miles east of downtown Los Angeles and 30 miles west of Palm Springs. The Banning Municipal Airport (BMG), a nontower field whose 4,955-foot Runway 8/26 is not served with any instrument approaches, has been open since April 1940. According to the Press-Enterprise, between 2010 and 2015, its traffic counts dropped 71.7 percent, to 1,324 from 4,674.

A community of 28,603, Banning, California, is 80 miles east of downtown Los Angeles and 30 miles west of Palm Springs. The Banning Municipal Airport (BMG), a nontower field whose 4,955-foot Runway 8/26 is not served with any instrument approaches, has been open since April 1940. According to the Press-Enterprise, between 2010 and 2015, its traffic counts dropped 71.7 percent, to 1,324 from 4,674.

Only 38 of its 61 hangars were occupied, and some were reported to be “in a dilapidated condition.” Interestingly, there are 38 single-engine aircraft based on the airport. At a city council meeting in April 2017, the public works director said the income from hangar rent and fuel sales covers the airport’s expenses, but “We don’t generate enough to improve buildings which are not FAA-eligible” for airport improvement grants.

After discussing ways the 154-acre airport might better serve its hometown, such as a logistics center with warehouses, the city council voted 4-1 to close the airport. The dissenting vote was the mayor pro tem, who was opposed because Banning hasn’t explored what investment would lure back airport business. With established full-service, all-weather GA airports like Palm Springs nearby, logic suggests that this would be an investment with little or no return.

Banning has begun the conversations with the FAA about closing the airport, a process that will likely take an unknowable number of years. FAA approval of a new airport is more predictable, which narrows the delivery date. The Metropolitan Knoxville Airport Authority submitted to the FAA its plan for a new general aviation airport at the East Tennessee Technology Park (ETTP) in April.

Banning has begun the conversations with the FAA about closing the airport, a process that will likely take an unknowable number of years. FAA approval of a new airport is more predictable, which narrows the delivery date. The Metropolitan Knoxville Airport Authority submitted to the FAA its plan for a new general aviation airport at the East Tennessee Technology Park (ETTP) in April.

The airport is already on the FAA list of eligible projects. If, as expected, the FAA approves the airport plan by the end of 2018, said the chairman of the airport authorities GA committee, construction will begin in in late 2018 or 2019, and in operation in 2021.

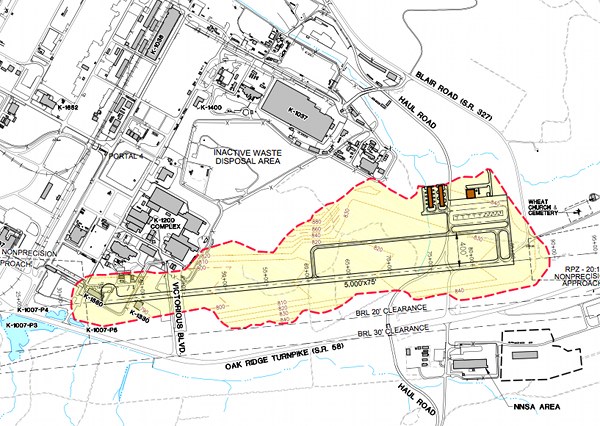

Building this airport has always been part of the reindustrialization plan for the 33,000-acre Oak Ridge Reservation, built during World War II as the military and administrative headquarters of the Manhattan Project. If approved, the new airport will cover 171 acres on the former K-25 site, where a 2-million-square-foot uranium enrichment building once stood. The single 5,000-foot runway and 40 hangars will complete the modes of transportation—road, rail, and river—that have served Oak Ridge since it was built.

“Airports have proven that they create jobs, grow economies, and stimulate prosperity,” said Bill Marrison, airport authority president. “The Oak Ridge Airport can be a crucial tool in the revitalization efforts underway” in the 200-acre Heritage Center Industrial Park, which includes a number of existing structures, and new structures that will rise on the Horizon Centers 1,000 acres of greenfield building sites.

It should not surprise anyone that this reallocation of airports will continue until there is a self-flying car in every garage. As the economic reallocation affects the lives of those general aviators who fly for pleasure, city councils nationwide will have their own Banning votes. And in the areas where businesses have reason to congregate, existing public-use airports will grow—or new airports will be conceived—to meet their business aviation needs. –Scott Spangler, Editor

Related Posts:

May 23rd, 2017 at 12:39 pm

Good story. I’ve flown out to Banning a couple of times and have studied this decline and am I saddened by the decrease in public use airports; which are an essential part of life to many aviation enthusiasts and local economies. An aviation enthusiast myself with over 8 years of studies in aeronautical sciences, I always believe in an alternative approach to preserving airports. Unfortunately in many cases, the love of money–overtakes the passions and dreams of others and their pursuit of happiness.