Making Like Maverick in an L-39

By Robert Mark on January 17th, 2024 | Comments Off on Making Like Maverick in an L-39By Rob Mark

An early scene in An Officer and a Gentleman, the 1982 movie about U.S. Navy recruits slogging their way through officer candidate school, has granite-tough Marine Gunnery Sgt. Foley (actor Lou Gossett Jr.) confronting candidate Zack Mayo (actor Richard Gere) nose to nose.

“Now why would a slick little hustler like you sign up for the Navy?” asks Foley.

Mayo’s response grabbed me. “Because I want to fly jets, sir!”

I’ve been flying jets for years as a corporate pilot, but not real jets to some … like fighter jets. When opportunity knocked with an offer to fly an Aero Vodochody L–39 Albatros (one “s” in the Czech spelling)—a single-engine bird still used as a basic trainer for some nation’s fighter pilots—I jumped at the chance. And I seldom thought much about Top Gun either (“Do some of that pilot stuff, Maverick”) before my first day of training at Gauntlet Warbirds, based at Aurora Municipal Airport (KARR) west of Chicago. In a nice-job-if-you-can-get-it situation, Greg Morris serves as Gauntlet’s owner and chief pilot (see “Pilots: Greg Morris,” December 2011 AOPA Pilot).

The panel on the L–39 is a conglomeration of normal gauges, except some, are labeled in English, and others still in Cyrillic.

The panel on the L–39 is a conglomeration of normal gauges, except some, are labeled in English, and others still in Cyrillic.

My goal in these Gauntlet jet-training sessions? Cram enough L–39 knowledge and skill into my brain to pass a type-rating checkride. With very little onboard deice equipment, the L–39 is, however, a VFR-only bird. In a non-U.S.-certified Experimental aircraft like the L–39, the end result is called an Experimental Aircraft Authorization. Morris explained that the Experimental moniker also prevents Gauntlet from charging for rides. A pilot with any kind of certificate can begin training right away in the familiarization course where dual instruction is $2,200 per hour. Only if a pilot chooses the complete course with a checkride is an instrument rating required. The total cost will vary according to the student’s experience level and can run from six to 20 hours. And almost before I could ask, Morris said, “The FAA allows P–51 rides, though, under a special exemption. If they’d grant us an exception, I’d need another L–39 immediately to handle the business.”

The Walk Around

Morris and I began with a walk around N992RT, a 1974 C-model Albatros. Other versions ready the L–39 for light-attack missions. On first glance at its near-stiletto nose, it’s clear the 10,300-pound Albatros is fast. Down low, maximum speeds can easily exceed 425 knots. However, this airplane is also designed with systems simple enough—and handling qualities docile enough—to allow no-jet-time aviators to confidently solo in as little as 15 hours. But good jet flying is still demanding. Morris says that his no-previous-jet-time customers usually need between 15 and 20 hours to complete the training. “You’d think pilot problems would be all about stick-and-rudder skills here,” he said. “But most of the time, problems pop up because students simply haven’t spent enough time with the books. They need to know the L–39’s systems and our profiles cold when they walk in the door.” Not much different than corporate flying.

Preflight means ensuring the controls move properly, the pitot probes are undamaged, the oil level is sufficient, and both engine intakes—so dark you always need a flashlight—are clear of debris. You scramble up the side of the Albatros before you climb in, where the L–39 seat is not comfortable, not even a little bit. But then, you’re sitting on a parachute and a disarmed ejection seat. I eventually did find some degree of comfort, even with that big, fat, five-point harness; a helmet; visor; and an oxygen mask.

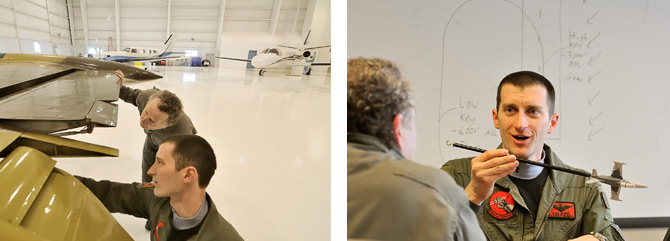

The author and Greg Morris review the aircraft flight envelope during ground school (right). The L–39’s Fowler flaps are clearly visible during the preflight inside Gauntlet Warbird’s hangar at Aurora Municipal Airport (left).

Many of the panel gauge identifications are written in Cyrillic, with metric scales, the panel looks much like that of a U.S.-built fighter jet—including the narrow and mildly pressurized (4 psi) cockpit. The big throttle on the left side includes a thumb-operated speed-brake switch to make extension and retraction of the boards beneath the belly easy. The checkout includes a brief on the L–39’s castering nose gear. Steering happens through coordinated use of brakeless rudder pedals augmented by a handbrake, which looks like it was swiped from a 10-speed bike, attached to the control stick. Need a right turn? Hold full right rudder and gently grab the handbrake. “That braking system is the single thing that gets everyone,” Morris told me. “I constantly get thrown around in the backseat while we’re on the ground as folks get used to it.” He joked, “That’s one reason I wear the helmet.”

The 3,800-pound-thrust Ukrainian-built AI25-TL engine needs an air-assisted start provided by the onboard Sapphire APU. Once it spins up the engine we begin taxi practice to the runway, something a bit akin to learning to steer my old taildragger. Like most jets, before-takeoff items are few, except for the slam check, where I shove the throttle from idle to full power to time how long it takes to reach full power, normally about 12 to 14 seconds, which is why you almost never, ever pull the throttle back to idle if you’re high or fast on final, for example, where speed brakes would be adding drag as well.

A Bit Like a Taildragger

I still zig and zag a bit with those brakes for the lineup and hold them while I run the engine to full power—106 percent—before releasing the brake handle. Steering is quite easy as we shoot down the runway. At 90 knots I ease the stick back and we’re through 140 knots with gear and flaps coming up before I know it. In a 200-knot climb, we’re rocketing at 3,000 fpm toward the VFR Gauntlet practice area west of Aurora Airport.

Morris was right. The L–39 is a breeze to fly—light and responsive on the controls. My 200-knot steep turns begin at 14,500 feet with gentle banks. Morris asks to show me a few. He effortlessly cranks that puppy into 45- to 50-degree banks. I try and now it’s really fun, even though the L–39 is clearly sensitive in pitch. “You really need to include the attitude indicator in your scan,” he tells me. “Even a small angular change from the horizon quickly translates into a huge velocity change.” I’ll need to work on these.

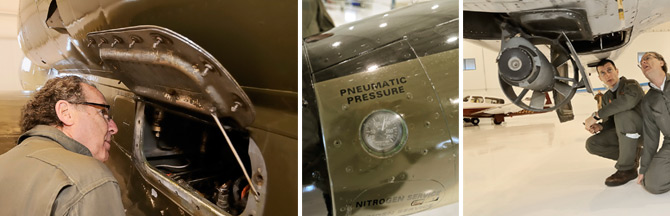

Preflight demands a check of the ram air turbine (right), pneumatic pressure (middle), and a look inside the variety of other access panels (left).

Next comes a roll looking out the huge glass canopy. Now I’m really loving this airplane. The stalls are very simple—wait for the buffet and recover. But a secondary stall awaits any pilot who recovers with too much back pressure, too quickly.

The traffic pattern is where the fun really begins as we try out the Albatros as a touch-and-go birds. I was almost exhausted after the first hour-long pattern session before I realized that bizjet pilots don’t normally fly VFR touch and go; approaches and go-arounds, yes, but not touch and goes. Because the Albatros can accelerate so quickly, Morris tells me to fly the upwind and prepare for a quick 180-degree turn back to downwind all at once, pulling the power back just before we reach pattern altitude.

Let the Nose Fall??

In the pattern, you can’t let the speed get away from you or the patterns become ugly, as Morris mentioned in the briefing. It sounded easy, but on the first few, I found myself with the power back, nose up high, and in a turn wondering what might be coming next. “Don’t try to hold everything up,” Morris instructs. “Just let the nose fall as you turn. If you don’t reduce the power quickly as you unload the nose, you’ll easily gain 70 knots turning downwind.” After a few tries, my turns plunk me right on downwind at just under 200 knots. “That’s perfect,” Morris announces. I began to breathe a bit as each landing started to improve on the last.

Reminding me of that slow engine spool-up time, Morris said we’d fly base at 140 knots with the speed brakes extended, demanding high power settings that prepare the engine for instant response in the event of a go-around. On short final, I slow to 120 knots and hold it off like a Cirrus. Some were even more fun as I held the nose up high for a little aerodynamic braking, just like those F–16s I always watch at AirVenture. On a touch and go, as soon as the nosewheel was down, I slammed the throttle in because of that spool-up time again. By the time I return the flaps to takeoff, we’ve reached 90, and the power’s back at max.

Reminding me of that slow engine spool-up time, Morris said we’d fly base at 140 knots with the speed brakes extended, demanding high power settings that prepare the engine for instant response in the event of a go-around. On short final, I slow to 120 knots and hold it off like a Cirrus. Some were even more fun as I held the nose up high for a little aerodynamic braking, just like those F–16s I always watch at AirVenture. On a touch and go, as soon as the nosewheel was down, I slammed the throttle in because of that spool-up time again. By the time I return the flaps to takeoff, we’ve reached 90, and the power’s back at max.

In L–39s, the last maneuver to learn is a Simulated Flame Out (SFO) approach, essentially like the instructor pulling back the throttle of a 172 to watch the pilot’s reaction. Since engine failures in fighters are likely to happen up high, simply looking out the window for a great field seldom works. A successful maneuver becomes all about energy management, so pilots don’t end up too high or too fast at the wrong time. Now the blackboard drawings Morris made illustrating Gauntlet’s SFO procedures made more sense. “Some people try to make up their own procedures when they’re nervous,” Morris told me. “When they eventually start flying the way we teach them, it usually all falls into place.”

The SFO practice actually begins near the airport at roughly 3,000 feet agl. Turn final two miles out at 200 knots and cross the numbers headed upwind, a point called High Key. Students set the throttle at 70 percent N1 and try to not touch it again until just before the touchdown. The pilot now blends only the use of flaps, gear, and speed brakes together with a pitch to make the runway. At the numbers, the pilot begins a single 180-degree turn back to downwind. At the Low Key point, opposite the numbers, it becomes easier to figure out whether the plan will work. Morris says a good instructor can see a successful SFO coming a half-mile away. I’m still working on mine.

And so the training hours passed and I eventually began to feel more comfortable in this tiny fighter-plane cockpit—now that I was accustomed to the myriad foreign-language dials and gauges, that is. In the end, the L–39—as slick as I thought it was during that first round of touch and goes—flies just like an airplane, a quite good one, of course, thinking back to a roll rate that could easily knock my eyeballs from side to side if I wasn’t careful. When I look back at checking out in a Cirrus SR22, I thought that, too, was quite an eye-opening experience at the time. Now that I was preparing for the check ride, I realized the L–39 too would someday become just another airplane in the list of those I’ve flown. Yeah, right, Maverick!

Robert Mark publishes Jetwhine.com. This story was reprinted here with permission of AOPA Pilot where it ran originally.

I saw the videos of the raging firestorm engulfing the A-350 on a runway before I heard any of the audio on Tuesday, so I assumed the accident had occurred here in America. From the pictures alone, the loss of life should have been mind-numbing. Considering how many close calls we had last year at major airports in the US, my assumptions were justifiable, some 19 serious near collisions. A serious near collision is about as close as two aircraft can come without metal scraping metal.

I saw the videos of the raging firestorm engulfing the A-350 on a runway before I heard any of the audio on Tuesday, so I assumed the accident had occurred here in America. From the pictures alone, the loss of life should have been mind-numbing. Considering how many close calls we had last year at major airports in the US, my assumptions were justifiable, some 19 serious near collisions. A serious near collision is about as close as two aircraft can come without metal scraping metal.

In English, that meant the pan that sits beneath the potty on the airplane must be removed by hand, a bit like sliding a broiler drawer out from beneath the oven at home. But the smell was worse—much worse. Just a few quick screws to loosen the box and out comes the pan. I quickly learned that the pan was nearly as wide as the cabin aisle itself. The trick, then, was not only knowing how to remove the stinkpot, turn around, and head down the aisle toward the front door. The real trick is to never, ever bump up against an armrest before you exit the cabin, because just so much as even the tiniest spill along the way meant both pilots might well be trying to clean the blue juice mess out of the carpet for hours.

In English, that meant the pan that sits beneath the potty on the airplane must be removed by hand, a bit like sliding a broiler drawer out from beneath the oven at home. But the smell was worse—much worse. Just a few quick screws to loosen the box and out comes the pan. I quickly learned that the pan was nearly as wide as the cabin aisle itself. The trick, then, was not only knowing how to remove the stinkpot, turn around, and head down the aisle toward the front door. The real trick is to never, ever bump up against an armrest before you exit the cabin, because just so much as even the tiniest spill along the way meant both pilots might well be trying to clean the blue juice mess out of the carpet for hours.